|

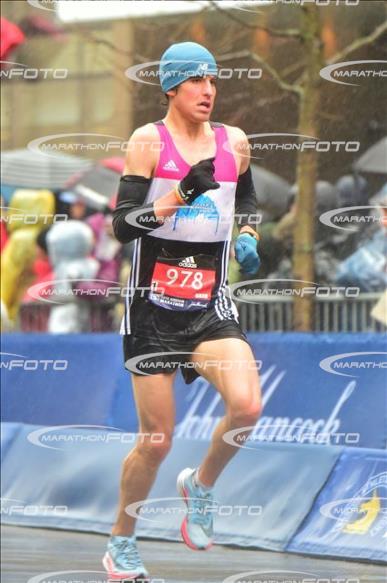

By Alex H. I am having trouble properly choosing a direction for the recap of my 2018 Boston Marathon experience, but I will dive right into the day and help anyone reading this get a better experience of the carnage they saw on their TV broadcasts. Heading into this race, I was the most confident I had ever been in my training and racing abilities as a marathoner. The mileage was higher, the long runs were longer and much faster, and the workouts were longer and more specific. That being said, with 30 mph headwinds and driving rain pellets, mixed with a 25 degree real feel, it was anyone’s day! I planned to take full advantage of the “anything can happen in these conditions” mentality I took with me to the line. As the gun went off, I established myself well and found a pack that was running a pace I have mastered over and over again in practice. Through the first few miles, my main objective was to stay keep pace with these complete strangers that I was sharing a life changing experience with. The pack mentality always helps a runner in such a long race, and on a day as windy as Monday, having people to break up the wind with was highly advantageous. Between miles 3 and 8, I moved from around 60th to 40th and eventually into the mid 30s. I was running with rhythm and poise, and trusting the weeks, months, and years of work that went into the preparation moments like these. I saw sponsored professionals that I recognized falling back closer and closer to my grasp. This is when I will share with you all that the feeling I got from confidently moving up towards elite territory was euphoric and I do not regret trusting the fitness I know I have worked so hard for. Through 10 miles, I truly thought it was going to be my day. And then things went south. By mile 11, a switch flipped, and I went from feeling smooth to feeling lethargic in a few steps. My hands were too numb to open my fueling packets (containing necessary calories for optimum marathon performance), and around mile 12 and 13 I started losing mental clarity and the awareness of my surroundings. I usually will take in at least 100 calories every 5 miles of a marathon, but could not take any nutrition after mile 10. The feelings of disorientation and confusion only heightened as I began to fade off of my pack. By mile 16, when the famous Newton Hills began, I was staring at my shoes instead of looking up to prevent dizziness and help keep balance. The latter parts of the race are all a jumbled blur, as my body used all extra energy that I would normally need to race hard, and held onto it to stop the hypothermic conditions I was experiencing from getting worse. At mile 25, a great friend of mine who lives in Boston was holding a sign for me and shouting my name, and that was just enough to get me to look up and drive to the finish. Shortly thereafter, I found myself wheelchaired into the medical tent where I spent the better part of an hour being fed beef broth with a straw and doused with heated blankets.

Directly after the race and until very recently, I considered the day a failure. I ran 12 minutes slower than my marathon PR, and was not able to place as high as I would have liked. It is the first race since college (three years) where I did not run faster than I have every ran before. But what I was able to accomplish is something that I cannot say I have done very often: I took a bold leap in my confidence as a competitor, and got everything out of my mind and body on the day. As an athlete, and really as a human being facing any tough task, our best is all we can ask. One of my good friends sent me my own quote I shared from the last blog post, “failure is only failure if we stop trying,” and that really made me smile. I can look myself in the mirror and say that I ran the best I could on April 16th, 2018 from Hopkinton to Boston, and nobody can take that away from me. In the future, where faster times and brighter days are ahead, I can look back on this day and thank the gritty experience for teaching me my limits and how to push past them. Onward.

0 Comments

By Calvin W.

Marathons are really long races. Long enough that it seems like a good strategy to have a good strategy for running them. And that’s what I’ve tried to do from my very first marathon…have a strategy…even if it hasn’t always been good. My first marathon was in 2013, Garden Spot Village Marathon, Lancaster County, PA. Back then, fueled by conviction from a JRC Growlers running buddy—Big Dave—that basically anyone can run a sub-4:00 marathon unless they’re walking, I went out at the pace I felt sure I could sustain…and steadily got slower and slower aaaand slower. I finished in 4:24:22. He’s still my running buddy. And he still runs way faster than me. It took me 2 more races to drop below the 4-hour mark for the first time in 2014. It took me another 2 years running 1-3 races a year to run sub-4:00 consistently. An element of my success was mastering negative splits in training. The inspiration began when I started hearing from other runners around me that the key to really good racing was negative splitting--running the second half of a race faster than the first half. The inspiration concretized when I started paying attention to elite athletes. At the 2014 Winter Olympics, speed skater Apolo Anton Ohno was the rage. Listening to the commentators describing his races, I heard them talk about how athletes like him deliberately keep their pace low enough to conserve energy, but fast enough to remain competitive with the front of the field. And all you had to do was watch their relaxed effort at the beginning of every event compared to their all-out effort at the end to know they consistently negative split. Since then I’ve gotten good at it. I warm up and run easy during the 1st quarter of every run. Then I start picking up the pace with each successive quarter until I finish. When I look at my personal stats for every race I’ve done since I started training with negative splits, I can see the same tendency—well, not exactly the same, but the first and last quarters are mighty consistent, and the halves are largely unwavering. I’m usually finishing my final quarter around 45 seconds faster than my first. My marathon PR was at Steamtown 2016 in Scranton, PA. I began the race pacing the entire first half 9.0 and finished the last mile doing 8.0. (N.b. I calculate pace in decimal minutes rather than minutes-seconds. I’m weird that way.) In fact, I can consistently finish my final mile pacing a full minute faster than my first quarter. Quiet Man Tom (Shawmont Running Club) recently said to me, I don’t understand why you don’t have faster marathon times when you can finish so fast. He’s not the only person to think something like that. Here’s what none other than Hal Higdon has to say: “Nobody runs 1 to 2 minutes per mile faster in the last few miles unless they have run the earlier miles way too slow. You need to learn how to pace yourself better” (Higdon). Now, who am I to contradict Hal Higdon? Well I’d like to contradict Hal Higdon. Maybe no one does…unless they train that way. Garden Spot Village Marathon is a hilly race and prides itself at being so. It also holds a special place in my heart because it was my first marathon. I didn’t quite know how hilly, but given that it was a local, spring race, I don’t think it would have mattered much. I was going to do it no matter what. Because of its sentimental value to me, it remains the only race that I’ve ever run more than twice--once a year for every year I’ve run competitively--5 times total. GSV is so hilly I have to be extra careful of my starting pace. In 2013, my first year, here was my pacing by quarters: 8.5, 8.9, 10.2, 12.8; 10.1 avg, 4:24:22. In 2014, I managed to slow down my start: 9.3, 9.0, 9.5, 9.3; 9.2 avg, 4:01:38. (The ups and downs are a reflection of the hilliness of the course.) Here’s 2015 (when I truly negative split the halves): 9.7, 9.2, 8.9, 9.3; 9.3 avg, 4:03:13. And 2016: 8.8, 8.8, 9.8, 12.7; 10.0 avg, 4:20:51. And, finally, 2017: 9.1, 8.7, 8.9, 9.3; 9.0 avg, 3:55:08. If you’re paying attention amid all the numbers, you’ve probably noticed that I wasn’t really accurate when I said I’m consistently racing with negative splits. I did say that GSV Marathon is hilly. But don’t miss the point: I’ve gotten pretty good at negative splitting everywhere else. Here’s my PR marathon (2016 Steamtown)--9.0, 9.0, 8.8, 8.3 (8.8 avg, 3:49:51)--and my penultimate PR (2017 Rehoboth Beach Marathon)--9.1, 8.8, 8.8, 8.5 (8.8 avg, 3:50:27). Those trends are reflected in my training and half marathons. Here’s where I contradict Hal Higdon. With GSV as evidence, when I go out even 0.3 minutes faster--the difference between my 2016 and 2017 paces, about 20 seconds per mile--I don’t finish as well and I’m much farther from negative splitting. So here’s my goal for 2018 on April 14: 9.2, 8.9, 8.6, 8.3 (8.8 avg, 3:49:50). I plan to marathon-PR and I actually plan to do it by more than 1 second even though that’s about 5 minutes faster than my 2017 time. Here are some other justifications for the strategy and my goals: My last training cycles have gotten faster and faster so I can certainly improve any race time over last year. The justification for the starting pace: GSV Marathon is just bad for going out too fast. The justification for the progression: I need not to increase my pace too much to conserve energy for the hillier 2nd half when I’m going to be more fatigued. And the justification for the finishing pace: I can finish pacing as fast as 8.0 based on other marathons and can consistently finish the last mile a minute faster than I started. So that’s the strategy. Let’s see how the execution goes. Higdon, Hal. “Choosing a Marathon Pacing Strategy.” TrainingPeaks, 13 Oct. 2015, https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/choosing-a-marathon-pacing-strategy/. By Mike T.

Frank Shorter had the full attention of the 6 people sitting closely, clinging on every word about his gold medal Olympic marathon win. The other 16,400 people running the half-marathon walked by oblivious to the fact that one of the greatest marathoners ever was sitting there dispensing advice and tactics that each of them could use. Yet, a lot of those same people will watch televised poker tournaments, but not track or a road race. Recreational soccer, tennis, basketball and baseball players usually have an encyclopedic knowledge of elite players and also tend to watch those sports even if it involves seeking them out at odd hours and with the broadcast in a foreign language. They can debate the finer points of technique, gear, the greatest players, and list specific records and important dates related to their sport. However, ask your typical runner who won Broad Street in 2017, the current mile world record holders and their times, or the most popular shoe worn by the top marathoners at the IAFF World Championships and you’d be met with a blank stare or the question what is IAFF? In case you’re wondering the answers are Dominic Korir and Askale Merachi for Broad Street, Hicham El Guerrouj (3:43.13) and Svetlana Masterkova (4:12.56) for the mile, and the Nike Zoom Vaporfly 4%. I’ll let you look up IAFF. So why should you learn about track and field or road racing? Why should you read about elite runners or watch a race? There are two major reasons. First, if you want to convince someone that your running isn’t serious and isn’t a sport, the easiest way to do that is to be unable to discuss anything about running. Because guess what? Soccer, tennis, basketball and baseball all include running as part of their sport. Not the major part either but a less important part that is a means to the end of scoring a point or goal. As a result, participants in those often believe that since running is part of their sport, it obviously isn’t a sport on its own. And since you can only run and don’t play soccer, tennis, basketball or baseball, you also are less of an athlete, if one at all. If you were a real athlete you would be playing their sport, where they not only run but do other things as well. Without some basic knowledge, you’re fending for yourself with no answers when you try to explain but the best runners, like Frank Shorter, have been there and have the answers to the questions your friends are asking. Second, have you ever been injured, wanted to run faster, lose weight, gain weight, get stronger, or have better form? All of these questions can be answered by looking at the elite runners from running’s past and present. Just watching a single race can show you simple things like what to wear and how to drink when running or more complex racing aspects from drafting and running the tangents to pacing tactics. Want to learn more? At your next race expo, attend a clinic and ask a few questions. Not only will you learn something but the next time someone says running isn’t a sport, you can make Frank proud. Disclaimer: The author has watched soccer matches in Portuguese, played in basketball leagues, enjoys playing cards, has a world-class golf slice and cheers for the Oakland Athletics. |

tHE ORC cOMMUNITYSince its founding, The Original Running Co. has been at the center of a proud community of runners in the Delaware Valley. This is a place where runners can come together and share their thoughts and ideas. CategoriesArchives

November 2022

|

Catch up with The Original Running Co.

|

|

For all fittings please arrive a minimum of 30 mins prior to close

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed